Q&A: Michele Oka Doner: How I Caught a Swallow in Midair Opening Celebration at PAMM

Miami, FL – March 24, 2016 – To celebrate the opening night of Michele Oka Doner: How I Caught a Swallow in Midair, museum trustees, Collectors Council and Young Collectors Council members were invited to toast the artist at a private reception at Pérez Art Museum Miami. Guests enjoyed d’oeuvres and cocktails while PAMM Director Franklin Sirmans made remarks introducing the exhibition and recognizing all who made it possible. Following the reception, guests went down to the bustling auditorium for an art talk between Michele Oka Doner and Brooklyn-based writer Rebekah Rutkoff. The auditorium was standing room only as the two discussed the exhibition’s presentation of functional designs, works on paper and ceramics inspired by natural forms. Michele Oka Doner: How I Caught a Swallow in Midair showcases a robust selection of artworks that span the duration of Oka Doner’s career and highlight major moments in her artistic development, revealing the lasting influence of the natural world on her practice.

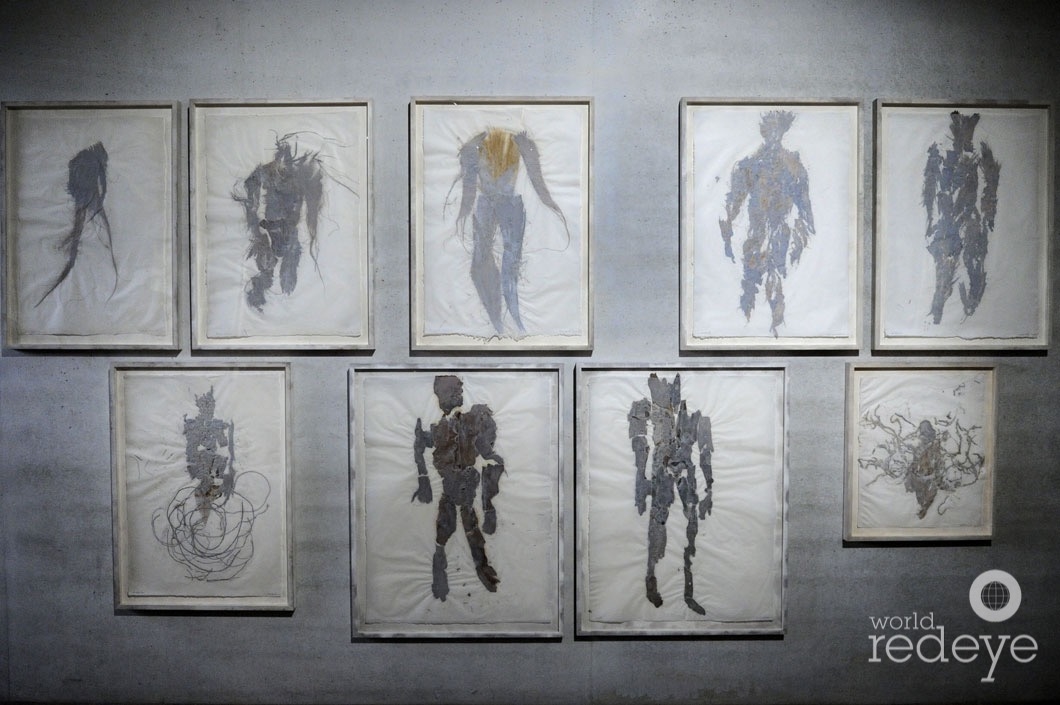

How I Caught a Swallow in Midair takes its name from a 1990 cyanotype, in which Oka Doner captured an organic abstract shape that could be easily mistaken for a swooping Swallow. In this work and others, the artist’s simple gestures transform aspects of the natural world—present but otherwise overlooked in day-to-day life—into poetic works of art. Handmade pieces blend with naturally occurring materials—porcelain resembling volcanic stone, stone resembling seashells, bronze sculpted into brambles and branches—while works on paper show the human figure made up of plants and other organic materials. Each of the roughly three-dozen pieces illustrates a pivotal turn in the artist’s career and was chosen in close collaboration between the artist and curator, making the exhibition an intimate portrait of her development over five decades.

WRE: To what early experiences and/or innate drives do you attribute your lifelong fascination and sustained engagement with the natural world?

MOD: I grew up in a time and place, Miami Beach, Florida, that was filled with pulsing, aggressive nature. One of my early memories engages all the senses. A huge mango tree dominated the backyard of our first home. Cycles of flowering, fruiting, and decay seemed to take up the entire space. From a child’s perspective, the tree occupied too much sky, blocking sunshine, creating deep shade. Countless fruits dropped seasonally, too numerous for a family to consume, and inevitably, the smell of rotted mangos entered one’s nostrils. Bees arrived in droves to feast on the sap and juice. To this day the scent of mangos trees in bloom stirs me, bringing me back to childhood, and leaves me somewhat uneasy.

Another primal memory centers on the sky. A tropical downpour arrived suddenly, with ferocity, while I was playing at the park. We ran for cover and as sheets of rain lessened into drops we made our way back to the car. Within what seemed like seconds, a bright sun was shining, the earth was gleaming, trees were glistening and dripping. I was confused by the speed of it all, the way it turned so abruptly, the force of driving rain, threatening gray clouds yielding to such vibrant blue. What I remember most was being unable to form a question that expressed my wonderment, and concerns, regarding the dissonances I had just experienced. Speaking of the senses, and the nose being the primary sense, I should mention the smell of Everglades burning. The dry years of the early 1950’s led to many fires that raged uncontrollably for days at a time west of Miami in the glades. Prevailing winds that swept across the Florida peninsula carried the ash and smoke. I would stand on the front lawn of our house and once again, try to fathom the forces of nature.

WRE: From childhood into early adolescence it was your ambition to be a biologist. Why did this change?

MOD: During adolescence I continued to enjoy, observe, the organic and unfolding developments in the world that was my envelop. I embraced with enthusiasm the subject of science at school. A remarkable teacher in junior high was able to put into words some of the excitement I had felt earlier. It is amazing how important language is when confronting the need, and desire, to understand and digest the magic of natural phenomena. Assigned by this teacher to choose a topic to follow during the course of the school year 1957-8, I chose The International Geophysical Year (IGY), an initiative that was a worldwide effort to learn more about oceans and planets. I read the newspapers, magazines such as National Geographic, and clipped articles about these adventures. I have both the resulting booklet, a rocket ship launching into space made for the cover, as well as a lifelong passion for geology, astronomy and oceanography.

It was after this, in high school, when I first looked into the microscope, that I understood the notion, the profundity, of biology, the science of life. The structure of cells, their growth and reproduction keyed into those early desires to understand and connect to the world I intuited. I conducted an experiment for a 10th grade science project in biology class, a series of marigold seeds planted in small clay pots and feed different diets, such as nitrogen deprivation, or acceleration by altering exposure to light sources. The seeds grew into plants that were stunning in their visual unlikeness to each other. Excited by the results, I went to great effort to present the project at the Science Fair. A piece of wood that echoed the shape of a flower pot was cut from plywood and then painted. A rim at the bottom of the implied pot was constructed to hold the marigold experiments. A Mission Statement was glued to the flat part. My father drove me to school as the resulting display was large and cumbersome. I carried the entire thing into the science room. The biology teacher laughed out loud and said something like: Oka, that looks as if it belongs down the hall in the art room. Perhaps the road diverged right there. I did go to the art room and even enrolled in class at Miami’s first art school on Biscayne Boulevard. There I began drawing with charcoal from life.

WRE: Your earliest mature work is sculpture in clay, a medium shunned by the leading artists of then dominant pop art and minimalism and scorned by establishment curators and critics of the period. Were you aware of the medium’s marginality in their world? And if so, how and why did you persevere?

MOD: My mother briefly taught Latin and though I never heard her speak Latin I understood her fluency with romance languages was due to the fact she held this knowledge. The grasp of Latin was necessary for medical school, botany, and many other disciplines. Clay is like Latin, a universal language that underpins artistic expression both historically and for many artists through modern times. I wanted to master it, and looked to Japanese culture for inspiration and encouragement. Japan was just emerging from warrior culture, having lost the war. Showing the west a new, different face, literature was translated and movies appeared at the art house theaters. I became fascinated by the history of their tradition as well as the simplicity of their approach, one that depended on, and honored, nature. There was rigor that demanded total concentration, immersion, and then, with competency acquired, one could release into the elements of chance, embodied by the raku kiln or salt glazing, where fire and water determined the outcome. The notion of Zen Master had the same allure for me as it held for the Beat Poets Gary Snyder or Alan Ginsburg, and for composer John Cage, whose throwing of dice to compose music resonated philosophically with the koans. “The closed fist receives nothing” became a Siren song, enticing me to continue along this path, to embrace the random with joy. I found in the study of clay earth itself, kaolins, the ball clays, the identification of the mines from which the clay was extracted, the oxides in the earth’s crust that provided the palette, the silica that fused in the fire to become a glaze. This was geology in my hands, chemistry lessons using the scales to measure and construct formulas for clay bodies, and slips and glazes. So many of the things I loved were made tangible.

WRE: Your love of collecting natural materials—living, dead, and inorganic—from botanical specimens and shells to stones and fossils, first begins to register strongly in projects like Seeds and Pods (1977-78). What was the impetus for translating these natural forms into ceramic?

MOD: I have always been a hunter-gatherer. First and foremost. Translating the finds into clay allowed me to expand the impulse. No longer was the peach pit extracted from the ripe stone fruit just detritus. I could take it to the studio, study the interior structure, and a landscape emerged. Bones from Cornish hen, ox tails, also were extracted from the nightly diner table to meet this scrutiny. (The vertebrate from the spine of the hen became a wondrous crown as seen in the Burial Pieces poster.) Seeds and Pods evolved over the course of a few years, and as I worked the intense awareness of form and ensuing consciousness moved me in the direction of Pictographs. I thought I could imagine, almost touch, the impulse to writing that sparked our ancient ancestors, that led to the first glyphs. I began to notice symbolic language everywhere, in branching twigs, twisted coral, water worn rocks and even the organs of our very human bodies.

WRE: In what sense do you consider the pieces in the series Pictographs “pictographs,” and how is the concept of “translation,” addressed above, relevant to their production?

MOD: I have always been interested in the origins of writing. According to Alexander Marshack’s The Roots of Civilization, the first marks created by humans were scratched into bones and recorded movement of the stars. (Coincidently, I recently discovered that Marshack began his journey of inquiry in the same cauldron of IGY that lite my fires.) Art, symbol and notation all have the same DNA. To associate image with writing enabled our ancestors to communicate as well as begin what we call history. With history came civilization. Pictographs became my own written record, a personal document of lingering investigations into the nature of things around me. I recorded ongoing thoughts on subjects such as germinating seeds: what do they look like as they sprout underground? How and when does the bud gave way to the flower? Some pictographs are virtually time lapse notions. On veins: note how the ones in our hands recall the veins in leaves, the tributaries and, especially deltas of rivers, as seen from above. Raku technique from a kiln I built bestowed immediate gravitas on these objects as the cracks lent the aura of age. Smoke from fire provoked from the red hot works pulled from the kiln seeped into the cracks. I was creating my own archaeology, developing language for life’s on going dialogue. Whereas the Seeds and Pods falls under the rubic of amulets, ritual objects that affirmed the fertility and continuity of life cycles, Pictographs were actually talking about it.

WRE: More than two decades passed between your work on the “tattooed dolls” and your more recent experiments with representation of the human figure. What was the impetus for your re-engagement?

MOD: I keep returning to the human figure, but I never really left it. Though a large project like A Walk on the Beach at Miami International Airport occupied much of my time, in fact, the two decades you reference, what is visible from the studio is a public work of art with pelagic imagery. On a smaller scale, as I work on the large projects, I also create pieces that can be completed in a sitting, an afternoon, a weekend. These compressed vehicles allow me a measure of satisfaction that comes with immediacy. They are more intimate. Often, these have been figurative. That said, the initial longing that initiated the Tattooed Dolls was to imagine humans as living coral. I would find torso shaped corals on the beach and see the human form. Years later, in Ann Arbor, I translated that impulse to clay. When I began to cast in bronze I could extend the vision. Scale gave more surface to develop the impulse. Cast bronze is not as fragile as clay so I could be more ambitious with texture.

Recently I had access to a large kiln at Nymphenburg in Munich and and created two life size figures from the iron rich red clay characteristic of Bavaria. I pressed tree and vine roots into the surface while they were still receptive and the resulting flow of linear mass evokes a profound connection to the growth of vegetation on earth. I named one of them Distraught Goddess and Her Prophesy, giving her voice as well as form.

Clay is like Latin, a universal language that underpins artistic expression both historically and for many artists through modern times.

Michele Oka Doner

Mooli Freiman, Tami Katz-Freiman, Mera & Don Rubell

Rebekah Rutkoff & Michele Oka Doner

Rebekah Rutkoff, Michele Oka Doner, & Tobias Ostrander

Tobias Ostrander

Rebekah Rutkoff & Michele Oka Doner

Michele Oka Doner

Sam Robin, Zaha Hadid, & Iran Issa Khan

Aaron Podhurst, Jorge Perez, & Franklin Sirmans

Aaron Podhurst & Franklin Sirmans

Cathy Leff & Jorge Perez

Aaron & Dorothy Podhurst

Maria Elena Ortiz & Valentina Gutchess

Frederick Doner & Michele Oka Doner

Michele Oka Doner, Paul Wilmot, & Denevin Miranda

Laura Raiffe, Catalina Roca, Peter Menendez, Cricket Taplin, & Lin Lougheed

Franklin Sirmans

Peter Mendez, Diane & Werner Grob

Jessica Katz & Laura Raiffe

Claudia Gehring & Maria Cunha

Roger Hines & Eva Silverstein

Pam Garrison & Victoria Cummock

Marcia & Pierre Levine

Matthew Goodrich & Susana Ibarguen

Tobias Ostrander, Bryan Cave, & Linda Cheverton Wick

Terri Schechter, Victoria Cummock, & Cathy Leff

Milagros Maldonado & Anabela Mendoza

Walid & Susie Wahab, Marlene & Nadim Ashi